Taste

On subjectivity, gatekeeping, and the risk of leaving words undefined.

“There is a time for any fledgling artist where one's taste exceeds one's abilities. The only way to get through this period is to make things anyway.” ➪ Gabrielle Zevin, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow

Taste is not purely subjective

People think taste is subjective, until they start to design things. Paul Graham argues that most people keep their thoughts on taste as unexamined impulses, starting from childhood. When they like something, they have no idea why—it could be because their friends like it, because it’s fashionable, or because a movie star uses it. Once they become designers, they start to realize the relationship between taste and good design. We all need to examine taste more objectively.

Taste is the ability to identify quality

To understand quality we need to look critically at: materials that are fit for purpose, ergonomy that considers audience needs, effective use of affordances, usability, accessibility, harmonic color choices, aesthetic choices that elicit emotion, intentional visual hierarchy—amongst others. Taste is in the observer, quality is in the object. The concept of taste becomes more productive when framed objectively around quality, and in ways that are measurable or at least comparable.

Taste is also curation

It is the ability to look at a wide scope of possibilities and choose with focus. In a world where Netflix launches hundreds of shows with questionable quality every month, film studio A24 has built their own brand based on supporting fewer movies that have a higher chance of (commercial and artistic) success. Taste, as a skill, is not exclusive to creators.

“My theory is that, as in chess, ‘taste’ is simply the ability to draw on patterns and experience to help us choose better candidates for analysis. An experienced designer doesn’t waste time on clearly ineffective solutions: typographically poor designs, bad colour choice, or unusable interaction metaphors. It follows that taste is learned, not innate. Experience, exposure, and practice give us patterns that suggest which solutions might fit which problems.” ➪ Cennydd Bowles

Taste can be developed

As any other skill, the best way to develop is practice: exploring new paths, taking risks, and making mistakes. Over time, we start to build a repertoire of things that work better than others—and most importantly, why.

Taste is not a matter of personal preference

I might prefer modernist architecture, you might prefer gothic architecture. Personal preference is not that relevant in design—you’re designing for a brand that has a specific aesthetic, and for an audience whose preferences might be different than yours.

Sometimes you’ll need to design products that don’t match your personal aesthetics preferences.

Fashion changes, taste doesn’t

Visual trends will always change (not only over time but across cultures). Think about how software design has evolved from skeumorphic to flat, or even shorter-lived trends such as glassmorphism or bento grids. Someone with a developed taste will know to appreciate good quality beyond the latest trends.

“Thinking about fashion as language allows you to appreciate the many and varied aesthetics in the world, and negotiate between personalization and ‘following the rules.’ There are rules in grammar, but also a great ability for personal expression (e.g., slang, ee cummings, etc).”

➪ Derek Guy

Taste separates humans from machines

In an AI-powered world, it’s never been easier to produce reasonably well-executed outputs in a short amount of time. When execution becomes commodity, developing taste to know what to create becomes a crucial skill.

Taste should not be used as gatekeeping

Watch out for people using “good taste” and “bad taste” as exclusionary terms. When someone says “you need to have good taste” but doesn’t break down what taste means in an objective manner, they might be using it as an excuse to exclude people. Historically, taste has been an elitist concept and intentionally kept blurry and subjective to prevent people from accessing certain places, groups, or opportunities.

“Everything that is beauty and standard in design is in support of the system︎. It’s an aid in reinforcing a constantly evolving (but no so much) mono-aesthetic︎. It participates in a gate-keeping of taste, making us all want and like the same things︎.” ➪ Margherita Sabbioneda

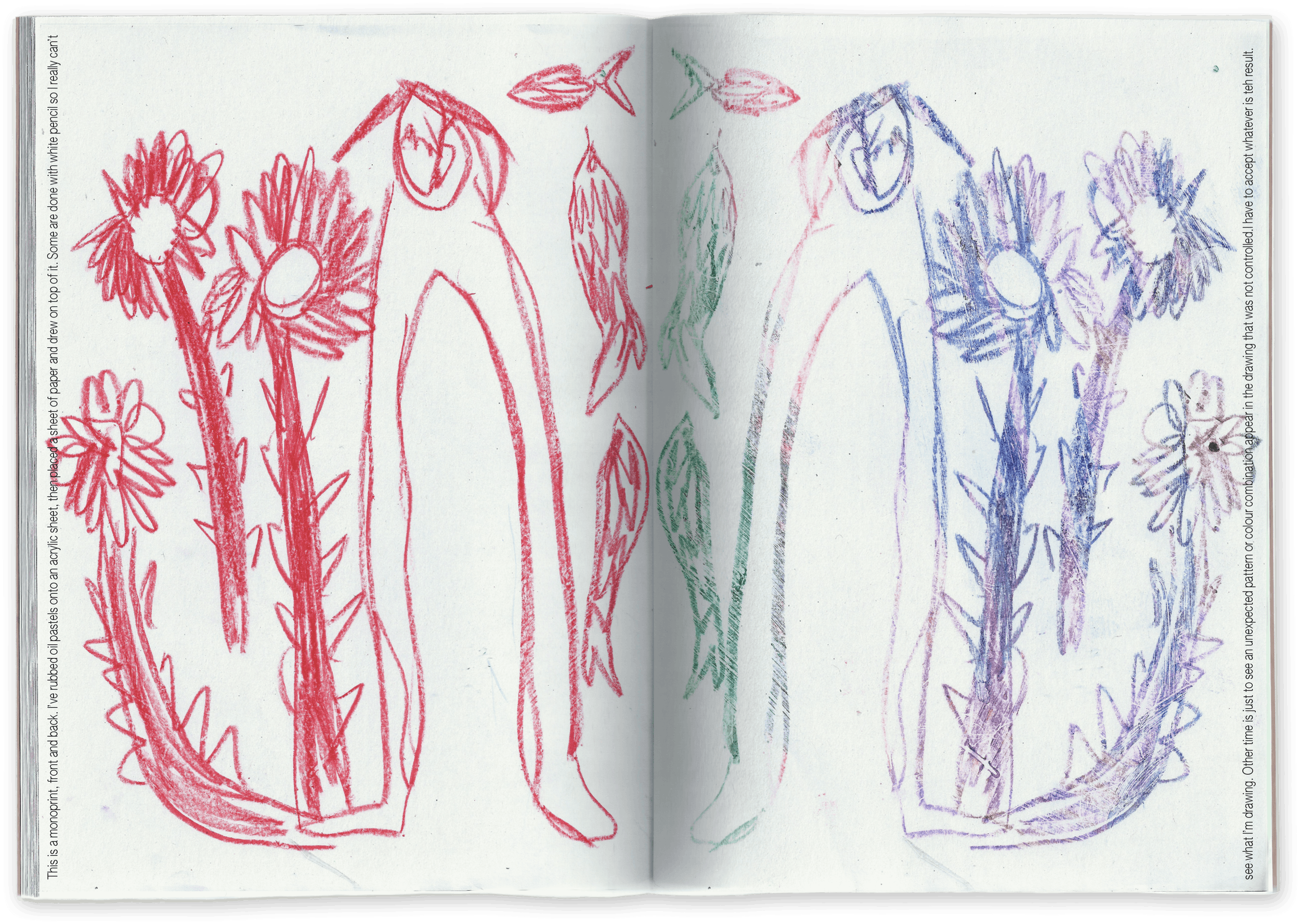

Book by Margherita Sabbioneda

Taste has to be demystified

As designers, we have to start objectively defining quality: what does quality mean for our company, our team, and our own careers as designers? How can we make design education less focused on process, and more focused on quality? When we eliminate blurry words and subjectivity from the conversation, our individual taste skills can finally be used to reach that shared quality goal.